What kind of political economy is hidden in the woods? Do we rely our future on myths, and on what cost? Can a box of matches give light and clearing to these questions? To find out, click and roll down.

’Metsästä – From the Woods’ by Anne Golaz

- Why do aspens sigh?

- They are afraid to be cut down and splintered into matches.

We are entering a mythological time, the end of the world, as we know it. By saying so, I mean that every tale, every epoch, and the constitution of history, requires an ending. In our current great narration, we are approaching one with hastening steps. While the end is getting near, it seems clearer that it is, either the end of the world, as we know it, or the end of us as the world used to know. Whether the ending has a beginning, is yet to be seen, or yet to be done.

The Finnish economy, as we used to know it a few decades ago, stood with two legs, one made of iron and one made of wood. While the iron has changed from hard(ware) to soft(ware), the wood is now known as ‘bio’, and these two legs are supposed to take Finland pass the finishing line. While the iron-one is limping in the race, in the latest bets the weight is put on the wooden leg. Not only is wood the beginning for all the prosperity, but also the end for all the trouble. It bends to housing, textiles, gasoline and plastics to begin with. Furthermore, it is renewable, since its source is the same as the source of our troubles: carbon extracted from the thin air. In the current debate, a growing forest is ought to consume carbon and harvested wood to deposits it.

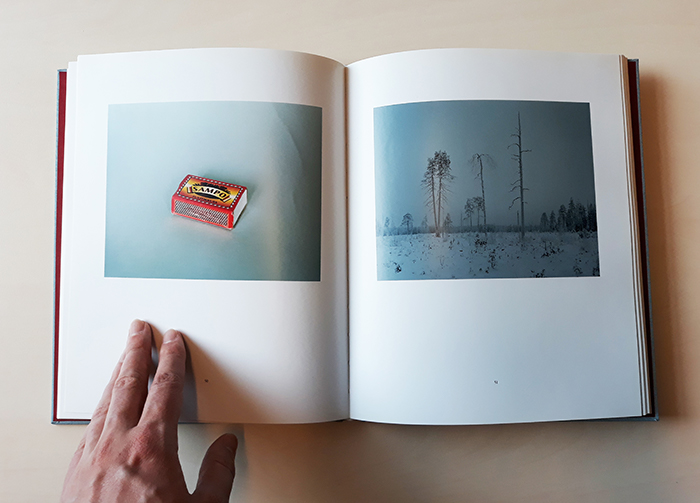

If I am to explain this phenomenon instead of using more than a 1000 words, I would do it by using, not one, but two pictures. In the book ‘Metsästä – From the Woods’ by photographer Anne Golaz, pages 50–51 show two independent but interlinked photographs, one presenting a matchbox and one a clearing. As the fire symbolises the civilization standing out from the nature, the matches present this story in a careless way while withholding all of its might, which is no child’s play. A greyish, bare and mundane appearance of the two photographs hides a story in an epic scale: the forest as the source of endless prosperity. In one word this is written to the cover of the matchbox – ‘ Sampo’. This mythical mill, in the core of the Finnish national epic ‘Kalevala’, could grind out from the air, salt, grain and gold, the three ingredients for wellbeing and prosperity. However, with what price? For the people of the North to achieve Sampo, the price was the maiden of the North. Sampo was the dowry made and given to the maiden’s family while she had to leave her home, the world she knew.

Neitä parka huokaiseikse, huokaiseikse, henkäiseikse, itse itkulle hyräytyi: Heitän suot sorehtijoille […] kanervikot kahlaajille […] Pellot heitän peuran juosta, salot ilveksen samota, ahot hanhien asua, lehot lintujen levätä (Kalevala 24: 297 – 299)

The world of salt, grain and gold is going to be a deserted one. Salted soil will not grow, grain will not bloom, and gold causes fever. For harnessing the forests for fast growth and optimized time of harvesting to improve its capacity for both economic production and depositing carbon will likely lead to high level of cultivation in forestry and therefore like in agriculture, to a certain level of monoculture. The photographs tell also an old side of the story. In clearcutting the forest has thinned into few standing sticks, after the trees have scattered to the ground like a pile of matches fallen to the floor. In the end, the prosperity had a price to pay: bioeconomy with a cost of biodiversity.

Jäivät lapset laulamahan; lapset lauloi jotta lausui: Lensi tänne musta lintu, läpi korven koikutteli, suostutteli meiltä sorjan, maanitteli meiltä marjan, otti tuo omenan meiltä, vietteli ve’en kalasen, petti pienillä rahoilla, hope’illa houkutteli. (Kalevala 24:479 – 488)

Myths are powerful. They are the legs in which we stand. What is then left from ours to choose, if we are ought to follow them step by step, to live them into reality in their totality? Or can we to learn from them, to avoid the wrongs, to find our way through the end and towards new beginning? A Chinese proverb says: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.”

PS: The last factory producing matches in Finland was closed in Vaajakoski in 2017.

Sources:

Anne Golaz (2012). Metsästä - From the Woods. Kehrer Verlag

Elias Lönnroth (2000) Kalevala 30th edition. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura: Helsinki

Maarit Piippo (2017). Paluu viimeiselle tulitikkutehtaalle. Kansanuutiset 24.12.2017.

Text by Joonas Vola,

The photo taken with the permission of the author of the book.