Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo reports from research in Sicily that she is currently working on together with native Sicilian Nuccio Mazzullo. In this scientific undertaking, the northernmost practice of reindeer herding is studied and compared with the seasonal movement of sheep flocks in Sicily, thereby connecting Europe’s northernmost and southernmost herding practices. The project also connects to Hannah’s own upbringing in the French Vosges mountains, where her family herded a flock of goats in the 1980s

The practice of transhumant pastoralism, i.e. the seasonal movement of livestock, has been decreasing across Europe for many decades. In the context of this continuous decline, the opportunity to study migratory sheep and goat herding practice is “imperative” (Greenfield, 1999). Transhumance is often defined as “life on the margins” (United Nations Peacekeeping, 2020) at least in the perception of people living in populated centres of towns and villages. But what we observe in Sicily is more like living in between – moving from and between private properties as well as public land, divided and connected by roads, fences, rivers and other landscape features, which have to be overcome by the shepherd and his animals in the need access available grazing ground. In this century-old practice, the herder guides the herd through a network of private properties. The transhumant path has to be chosen according to the cultivation cycle and in agreement with farmers: where the agricultural land has been harvested, the herd will feed on the remains of harvested crops, such as wheat, and fertilize it with dropping in return.

Staying connected: the herder’s social life

Where this movement through the land once used to be an activity of complete solitude – only the herder and the herd moving around for days without possibility to see or talk to their families – this has certainly changed with the widespread use of mobile phone technology. In the fourth picture below, for instance, we met a herder and his herd who had come from inaccessible parts of the coastal land. The herder had reached the road only minutes before a woman arrived by car to meet him and bring his lunch. Vidal-González and Fernández-Piqueras (2020) take account of this transformation of transhumant culture, when previously the herders were isolated from family and friends for many days, whereas now the long period of solitude is disrupted by flexible meetings arranged in rhythm with the routines of herders as well as their families. Herders are thus more integrated into society today, however, the image of the outsider prevails.

Path-finding skills: Sapersi muovere (knowing how to move)

A herder’s path-finding skills are based on his knowledge of the landscape, his acquaintance with land owners, the needs of agricultural crops and their cycles. With some land owners it may be difficult to agree on migration over their land, which can be quite disruptive, thus, requiring more negotiation and bartering of goods (cheese) in exchange for the use of the land. The anger and potentially violent response of armed owners is to be considered. Many herders have been killed in the past, vulnerable as they move alone with the animals. It is a rough life, because of the need to use resources that others own albeit no one requires. This is the case also in other parts of Italy as we can gather from Allovio’s remark about the shepherds in the region of Piedmont in the north of Italy:

“Molti contadini della zona [da Nizza ad Asti] esprimevano ed esprimono valutazioni non certo positive sui pastori transumanti: ladri d’erba per far mangiare le bestie, ladri dei pali delle vigne per fare il fuoco, irrispettosi delle proprietà private, sospetti per il loro continuo girovagare. Certo, le pecore producono ottimo concime naturale che può far comodo a molti coltivatori e questo è uno dei motivi per cui alcune cascine ‘tenevano pastori’.” (Stefano Allovio in Sapersi muovere, Aime et al., 2001, p. 10)

“Many farmers of the area [on the route Nice-Asti] expressed and still express their judgements about transhumant pastoralists which are certainly not positive: thieves of grass, in order to feed the animals, thieves of vine poles to make campfires, they are disrespectful of private property, suspects because of their continuous moving around. Of course, the sheep produce excellent natural dung, which is very convenient for many agriculturalists and this is one of the motives why some dairy farms ‘keep shepherds.” (Stefano Allovio in Sapersi muovere, Aime et al., 2001, p. 10, own translation HSM)

Transhumance and modern agriculture

The land available for transhumance in Sicily has shrunk significantly. The expansion of intensive agriculture with heavy reliance on fertilizers has made the traditional triannual rotation obsolete and besides, agricultural farmers can easily do without sheep droppings. Previously, sheep herds would graze on vast expanses of recovering land within this triannual cycle. The decrease in available grazing land has consequently turned the transhumant pastoralism towards more locally confined, intensive feeding and breeding practices.

Transhumance in Sicily today: a fascinating practice

In this context of agricultural transformation, the transhumant practice has become difficult to pursue. In Sicily, pastoralism is still more practised in the central and more mountainous part of it where routes are less disconnected. To observe the skill and know-how of herders moving in the heavily fragmented and intensively harvested coastal areas of the island is a fascinating and impressive research undertaking.

Sheep grazing after the wheat has been harvested

(picture credit Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo).

Sheep walking home to be milked (picture credit Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo).

Sheep with full udder (picture credit Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo).

Shepherd meeting a relative during lunch break, exchanging news

(picture credit Nuccio Mazzullo).

Sheep feeding on harvested land (picture credit Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo).

A small herd of goats feeding on the road side (picture credit Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo).

My own early herding experiences: my father and I with one of our twenty

goats in the Vosges mountains (France). On about fifteen hectares of land,

the herd was feeding on forests and meadows. Neighbours protected

their vegetable gardens with fences. Picture credit Dagmar Strauss.

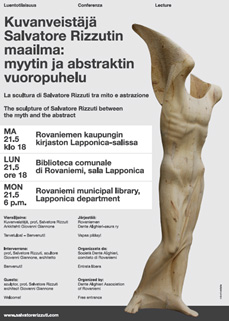

PS: A Sicilian sheep herder and artist visited Rovaniemi in 2012: Salvatore Rizzuti, a shepherd who spent his time carving wood when herding sheep.

See our forthcoming article:

- Nuccio Mazzullo and Hannah Strauss-Mazzullo (forthcoming May 2022): From Nomadism to Ranching Economy: Reindeer Transhumance among the Finnish Sámi. In: Letizia Bindi (ed) Grazing Communities. Pastoralism on the Move and Biocultural Heritage Frictions. Foreword by Tim Ingold, afterword by Cyril Isnard. Berghahn books: Oxford.

References:

- Aime, M., Allovio, S., & Viazzo, P. P. (2001). Sapersi muovere. I pastori transumanti ti Roaschia. Meltemi.

- Greenfield, H. J. (1999). Introduction. In L. Bartosiewicz & H. J. Greenfield (Eds.), Transhumant Pastoralism in Southern Europe. Recent Perspectives from Archaeology, History and Ethnology (pp. 9–12). Archaeolingua.

- United Nations Peacekeeping. (2020). Preventing, Mitigating & Resolving Transhumance-Related Conflicts in UN Peacekeeping Settings. A Survey of Practice. United Nations Departments of Peace Operations.

- Vidal-González, P., & Fernández-Piqueras, R. (2020). Connected solitude: Mobile phone use by Spanish transhumant livestock farmers. Mobile Media & Communication, 9(2), 377–396.